Albert William Williams, Private, 1st/2nd Battalion Monmouthshire Regiment

In the 1891 census Albert Williams is recorded as a visitor at Weston Road, Stansbatch, Pembridge. He is four years old. The head of the house is Samuel Morris who is a wheelwright and carpenter who is married to Elizabeth Morris. Albert and Elizabeth Morris are both in their early 40s and have two sons and two daughters between the ages of 8 and 12.

Ten years later, Albert Williams is residing at Field Cottage, Lyonshall where he is described in the 1901 census as a boarder.

Photo above: Field Cottage, Lyonshall today (1)

He lives with John Hollins (46) who works as a “general labourer on farm” and John Hollins’s wife, Milbrow (51). Both John and Milbrow Hollins had been born in Lyonshall.

At some point, they become Albert Williams’ foster parents.

In June, 1909, Albert Williams, then 19 years and six months old, signs an oath of attestation of service for four years in 2nd Battalion, Monmouthshire Regiment. This attestation states that his trade is as a collier and that he is employed by a colliery in Ebbw Vale.

Above photo: Marine Colliery, Ebbw Vale, 1907 (2)

At the time of his attestation, his address was 50 High Street, Pontypool.

Above photo: High Street, Pontypool, circa 1920s (3)

In June, 1913, when his four year period of enlistment in The Monmouthshire Regiment was up, he re-engaged for a further two years of service.

The 2nd Battalion, Monmouthshire Regiment was based at Osborne Road in Pontypool.

“Recruits to the Territorial Force carried out preliminary training at their unit’s depot and would then attend evening and weekend drills and, if possible, the summer camps.

The Territorial Force men were not liable for foreign service, unless they volunteered. Albert Williams did that.

When war was declared in August 1914, the battalion was at once mobilised and moved to defend Pembroke Dock. By 11th August, they moved to Oswestry and by the beginning of September they were at Northampton.

They proceeded to France as part of The British Expeditionary Force on 7th November, 1914 landing at Le Havre to join 12th Brigade, 4th Division.” (4)

The battalion then spent the winter taking part in trench warfare near Armentieres.

Above photo: Battle of Armentieres. Trench of the 'C' Company, 1st Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles,) 1914. (IWM)

The battalion subsequently took part in the Second Battle of Ypres fighting alongside the 1/1st and 1/3rd Monmouths in the 28th Division.

“During the First World War, the Second Battle of Ypres was fought from 22 April – 25 May 1915 for control of the tactically important high ground to the east and south of the Flemish town of Ypres in western Belgium. The First Battle of Ypres had been fought the previous autumn.

The Second Battle of Ypres witnessed the first mass use by Germany of poison gas on the Western Front.

Above photo: Anti-gas measures, Ypres (IWM)

The advent of the use of gas on the battlefield (the British Army were to employ gas at the Battle of Loos in September) prompted both sides to begin developing more effective gas protection.

Following the Battle of Loos, at Ypres, Allied forces were initially provided with cotton pads to cover their mouths, soaked in chemicals or sometimes urine, and goggles. Over the course of the war, more effective respirators were developed.” (IWM)

“Such were the losses (after the 2nd Battle of Ypres) that the three (Monmouthshire) battalions were temporarily amalgamated.

Above photo: Ypres after the 2nd Battle of Ypres (Wikipedia)

By July 1915, the 1/2nd had been brought up to strength and resumed its own existence. By May 1916, 1st/2nd Battalion, Monmouthshire Regiment were now part of 29th Division.

From late March 1916, the 29th Division was put into the British Front in the area north of the Ancre River, near to the German-held village of Beaumont Hamel. For the following three months, the battalions in the division spent their time doing tours of trenches and training behind the lines to prepare for the large British offensive against the German position planned for the end of June.

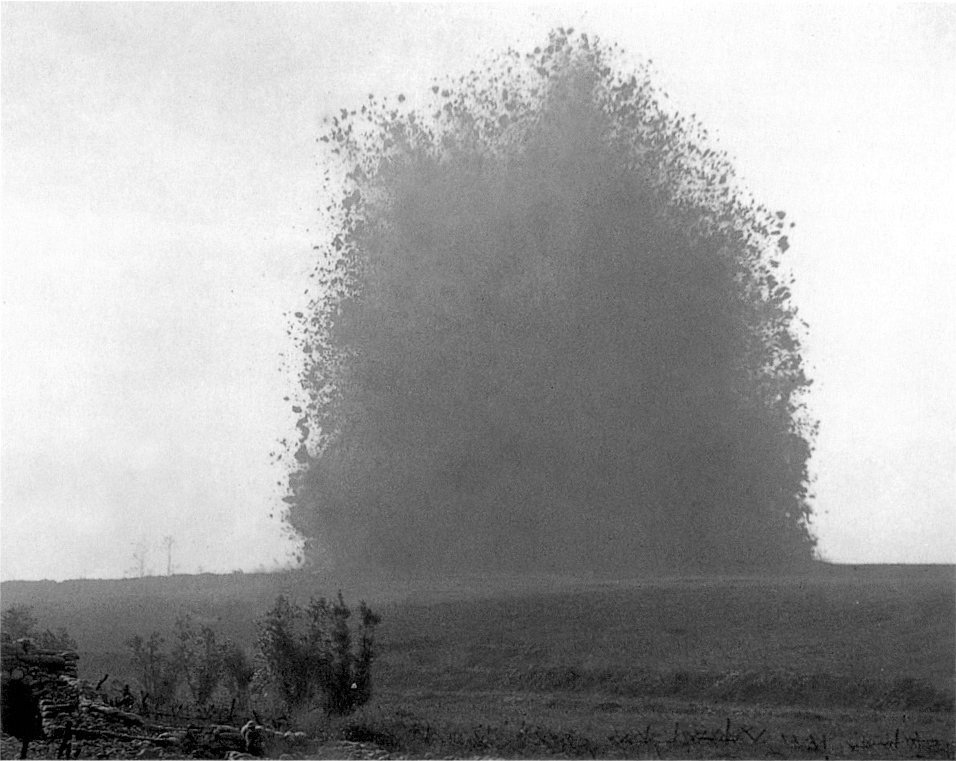

Following a 7-day artillery bombardment of the German front and rear areas, the battalions of the 29th Division were in position in their Assembly Trenches in the early hours of Saturday 1 July.” (Wikipedia) “At 07:20 hours the huge Hawthorn mine was blown on the left of the division's position.

Above photo: Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt (IWM)

The leading battalions in the attack left the British front-line trench at 07:30 hours.

Above photo: Troops resting in a communication trench during the opening hours of The Battle of The Somme (IWM)

The British casualties were severe, with many men never reaching the German front line.” (4)

In 1917, the 1st/2nd Monmouthshire Regiment were in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Battle of Scarpe during the Arras offensive.

“The Battle of Arras (also known as the Second Battle of Arras) was a British offensive on the Western Front during the First World War. From 9th April to 16th May 1917, British troops attacked German defences near the French city of Arras on the Western Front. The British achieved the longest advance since trench warfare had begun, surpassing the record set by the French Sixth Army on 1st July 1916. The British advance slowed in the next few days and the German defence recovered. The battle became a costly stalemate for both sides and by the end of the battle, the British Third Army and the First Army had suffered about 160,000 casualties and the German 6th Army about 125,000.” (Wikipedia)

Above photo: British troops marching up to the trenches at Arras (IWM)

On 5th May, 1917, Albert Williams died of gun shot wounds to the abdomen at a Clearing Station at Pas de Calais. His journey there would have been similar to the following -

“Regimental Aid Post (RAP)

The RAMC [Royal Army Medical Corps] chain of evacuation began at a rudimentary care point within 200-300 yards of the front line. Regimental Aid Posts [RAPs] were set up in small spaces such as communication trenches, ruined buildings, dug outs or a deep shell hole. The walking wounded struggled to make their way to these whilst more serious cases were carried by comrades or sometimes stretcher bearers. The RAP had no holding capacity and here, often in appalling conditions, wounds would be cleaned and dressed, pain relief administered and basic first aid given.

Above photo: Regimental Aid Post (Wellcome Collection)

If possible men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground, and under shell fire, to the ADS.

Advanced Dressing Station (ADS)

These were set up and run as part of the Field Ambulances [FAs] and would be sited about four hundred yards behind the RAPs in ruined buildings, underground dug outs and bunkers, in fact anywhere that offered some protection from shellfire and air attack. The ADS did not have holding capacity and though better equipped than the RAPs could still only provide limited medical care.

Above photo: Outside an ADS (NAM)

Casualty Clearing Station (CCS)

These were the next step in the evacuation chain situated several miles behind the front line usually near railway lines and waterways so that the wounded could be evacuated easily to base hospitals. A CCS often had to move at short notice as the front line changed and although some were situated in permanent buildings such as schools, convents, factories or sheds many consisted of large areas of tents, marquees and wooden huts often covering half a square mile.

Above photo: Casualty Clearing Station (IWM)

A CCS would normally accommodate a minimum of fifty beds and 150 stretchers and could cater for 200 or more wounded and sick at any one time. Later in the war, a CCS would be able to take in more than 500 and up to 1000 when under pressure. Initially the wounded were transported to the CCS in horsedrawn ambulances – a painful journey, and over time motor vehicles or even a narrow-gauge railway were used. Often the wounded poured in under dreadful conditions, the stretchers being placed on the floor in rows with barely room to stand between them.” (5)

Given that Albert Williams died on 5th May from wounds, it is likely that he received these wounds at the 3rd Battle of Scarpe (3rd- 4th May 1917).

“The Third Battle of the Scarpe near Arras in Northern France over the 3/4 May 1917 resulted in the British Army suffering nearly 6,000 men killed for little gain. The official history of the engaged Corps stated:

“The confusion caused by the darkness; the speed with which the German artillery opened fire; the manner in which it concentrated upon the British infantry, almost neglecting the artillery; the intensity of its fire, the heaviest that many an experienced soldier had ever witnessed, seemingly unchecked by British counter-battery fire and lasting almost without slackening for fifteen hours; the readiness with which the German infantry yielded to the first assault and the energy of its counter-attack; and, it must be added, the bewilderment of the British infantry on finding itself in the open and its inability to withstand any resolute counter-attack.” (6)

Albert Thomas might well have been a casualty of this German counter-attack. He was 30 years old at the time of his death.

He is buried at Duisans British Cemetery, Etrun, Pas de Calais.

Above photo: Duisans British Cemetery, Etrun, Pas de Calais (CWGC)

“Most of the graves relate to the Battles of Arras in 1917, and the trench warfare that followed. From May to August 1918, the cemetery was used by divisions and smaller fighting units for burials from the front line.

There are now 3,206 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War buried or commemorated at Duisans British Cemetery.” (CWGC)

In the UK, WW1 Pensions and Ledgers Index Cards, there is a card relating to Albert Williams.

On the right-hand side at the top, it states “Particulars of Claimant(s)” and beside the “Name” is written “Hollings Mr John”. Below that is his “Address” and next to that is written “Lyonshall, Herefordshire” and below that is “Relationship” and next to that is written “Foster Father”.

It is not known when “John Hollings” (Hollins) made the decision to foster Albert Williams. As mentioned, in the 1901 census, Albert Williams was described as a “boarder” residing with the head of the property, John Hollins and his wife Milbrow at Field Cottage, Lyonshall. It’s possible that John Hollins and his wife had already decided to foster Albert Williams there and then. John Hollins and Milbrow Hollins were childless. Possibly, that played a part in their decision to foster him.

In 1917, a few months after Albert Williams had died, John and Milbrow Hollins were living at Moseley Common, Pembridge. Prior to that, in 1911, while Albert Williams was working as a coal miner at a colliery in Ebbw Vale, they had both resided at Rhodds on the Elsdon Estate in Lyonshall.

By 1919, their address was New Street, Lyonshall.

John Hollins died in 1932 at the age of 76 and Milbrow Hollins died in 1936 at the age of 87.

Rory MacColl

Sources

1/ https://www.oneoffplaces.co.uk/Field-Cottage-Herefordshire

2/ https://www.peoplescollection.wales/items/19444#?xywh=-12%2C-41%2C772%2C621

3/ https://blaina.gwentheritage.org.uk/

4/ https://www.wartimememoriesproject.com/greatwar/allied/regiment.php?pid=17680

5/ https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/evacuation-of-the-wounded-in-world-war-i/

6/ https://www.sofo.org.uk/objects-and-stories-the-missing-officer/