William Joseph Morgan, Private, 95th Machine Gun Corps

The 1891 census states that Joseph Morgan, born in 1886, was residing with his two parents, Thomas and Mary Morgan and four brothers and one sister in a four room (including kitchen) dwelling at Stansbatch in the parish of Pembridge. His father had been born in Almeley and his mother along with Joseph and his siblings had been born in Meer, Woonton. His father, Thomas, was an agricultural worker.

In the 1901 census, Joseph Morgan is still residing in the same dwelling. His father is now described as an estate worker. Joseph is fourteen years old. In 1911 the school leaving age was twelve but many children left school at ten. Joseph, it appears, is not employed nor a scholar.

By 1911, the records for Joseph Morgan become sketchy. It is possible that he was residing in Garston, Lancashire as a boarder and employed as a railway guard.

The “UK Soldiers Died In The Great War” directory states that he enlisted at Ammanford in 1915 in The Welch (Welsh) Regiment, service number 33761.

At some point, Joseph Morgan transferred to 95th Machine Gun Corps. This would not have been until October 1915, at the earliest, as the Machine Gun Corps did not come into existence until that date.

“The Machine Gun Corps (MGC)

In 1914, all infantry battalions were equipped with a machine gun section of two Machine Guns (MG), which was increased to four in February 1915. The sections were equipped with Maxim guns, served by a subaltern and 12 men. The experience of fighting in the early clashes and in the First Battle of Ypres had proved that the MG required special tactics and organisation. On 22 November 1914, the BEF established a MG School in France to train new regimental officers and machine gunners, both to replace those lost in the fighting to date and to increase the number of men with MG skills. A MG Training Centre was also established at Grantham in England.

Above photo: 131st Machine Gun Company, receiving training on the Vickers machine gun at Belton Park Camp, Grantham, Lincolnshire in 1915 (IWM)

On 2 September 1915 a definite proposal was made to the War Office for the formation of a single specialist MG Company per infantry brigade, by withdrawing the guns and gun teams from the battalions. They would be replaced at battalion level by the light Lewis machine guns and thus the firepower of each brigade would be substantially increased.

Above photo: Machine gun training at Belton Park Army Machine Gun Training Depot, Grantham (1)

The Machine Gun Corps (MGC) was created by Royal Warrant on October 14 followed by an Army Order on 22 October 1915. The companies formed in each brigade would transfer to the new Corps. The pace of reorganisation depended largely on the rate of supply of the Lewis guns but it was completed before the Battle of the Somme in 1916. A Base Depot for the Corps was established at Camiers.

The Vickers machine gun was fired from a tripod and was cooled by water held in a jacket around the barrel. The gun weighed 28.5 pounds, the water another 10 and the tripod weighed 20 pounds. Bullets were assembled into a canvas belt which held 250 rounds and would last 30 seconds at the maximum rate of fire of 500 rounds per minute.

Above photo: A Vickers machine gun team from the Machine Gun Corps (MGC) wearing PH Type anti-gas helmets in action near Ovillers during the Battle of the Somme, July 1916 (IWM)

Two men were required to carry the equipment and two the ammunition. A Vickers machine gun team also had two spare men. In 1914 the light Lewis gun was in experimental stage. It was a shoulder-held air-cooled light automatic weapon weighing 26 pounds and loaded with a circular magazine containing 47 rounds. The rate of fire was up to 700 rounds per minute, in short bursts. At this rate, a magazine would be used up very quickly. The Lewis was carried and fired by one man, but he needed another to carry and load the magazines. Lewis guns were supplied to the army from July 1915. The original establishment was 4 per infantry battalion but by July 1918, infantry battalions possessed 36.” (2)

Above photo: Lewis machine gunner (IWM)

“Units from the Machine Gun Corps were responsible for offensive and defensive fire support so were always a prime target for enemy fire. Wartime casualties were so heavy (62,000 out of 170,000 officers and men) that the corps was nicknamed the 'suicide club'.” (NAM)

In the “UK WW1 Pensions Ledgers and Index Cards”, it states that Joseph Morgan was a driver in the MGC.

The following describes what was involved in this role.

“The Drivers of the limbered wagons were part of the MG Section and operated as such.

Above photo: Limbered wagon (AWM)

The transport drivers of the limbered wagon and Small Arms Ammunition cart should be frequently exercised with the section, in order that they may thoroughly understand the necessity for taking advantage of ground to reduce visibility and may learn to act on signals to move as required. They should also be taught to fill belts by hand and with the machine, and in addition should receive sufficient instructions in the duties of the gun numbers to enable them to replace casualties in an emergency.” (3)

In 1916, 95th Machine Gun Corps as part of 5th Division, was involved in The Battle of The Somme including Guillemont and Flers de Courcelette.

Above photo: The Battle of Flers Courcelette 15 -22 September, Canadians testing a Vickers machine gun (IWM)

In 1917, 95th MGC fought at The Battle of Arras including at Vimy Ridge and The Capture of Vimy Wood.

Above photo: Gunners of The Machine Gun Corps fire their gun at a German aircraft, Battle of Arras 1917 (IWM)

It is not known where and when Joseph Morgan received the wounds that were to take him back to England. But given that a war gratuity of over £22 was granted to him (see below) after his death, it is very likely that he saw action with 95th MGC at The Third Battle of Ypres, including The Battle of Polygon Wood in late 1917.

Above photo: Menin Ridge, 3rd Battle of Ypres (Wikipedia)

And also, in 1918, he might well have seen action at The Battle of The Lys (Hazebrouck and Nieppe Forest).

When and wherever Joseph Morgan received his wounds, the journey back to England to receive the requisite medical attention would have been a precarious one.

The First World War created major problems for the Army’s medical services. A man’s chances of survival depended on how quickly his wound was treated. In a conflict involving mass casualties, rapid evacuation of the wounded and early surgery were vital.

Joseph Morgan would have journeyed back to England in several stages.

“Regimental Aid Post (RAP)

The RAMC [Royal Army Medical Corps] chain of evacuation began at a rudimentary care point within 200-300 yards of the front line. Regimental Aid Posts [RAPs] were set up in small spaces such as communication trenches, ruined buildings, dug outs or a deep shell hole. The walking wounded struggled to make their way to these whilst more serious cases were carried by comrades or sometimes stretcher bearers. The RAP had no holding capacity and here, often in appalling conditions, wounds would be cleaned and dressed, pain relief administered and basic first aid given.

Above photo: Regimental Aid Post (Wellcome Collection)

If possible men were returned to their duties but the more seriously wounded were carried by RAMC stretcher bearers often over muddy and shell-pocked ground, and under shell fire, to the ADS.

Advanced Dressing Station (ADS)

These were set up and run as part of the Field Ambulances [FAs] and would be sited about four hundred yards behind the RAPs in ruined buildings, underground dug outs and bunkers, in fact anywhere that offered some protection from shellfire and air attack. The ADS did not have holding capacity and though better equipped than the RAPs could still only provide limited medical care.

Above photo: Outside an ADS (NAM)

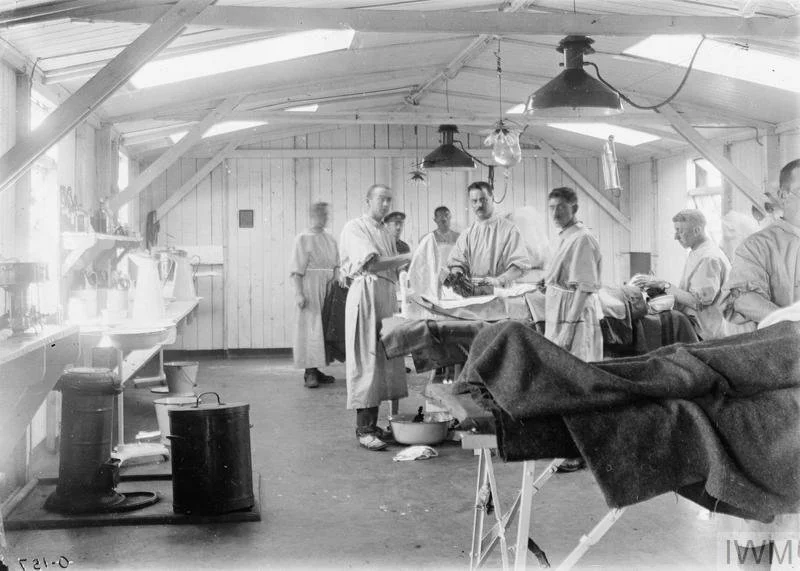

Casualty Clearing Station (CCS)

These were the next step in the evacuation chain situated several miles behind the front line usually near railway lines and waterways so that the wounded could be evacuated easily to base hospitals. A CCS often had to move at short notice as the front line changed and although some were situated in permanent buildings such as schools, convents, factories or sheds many consisted of large areas of tents, marquees and wooden huts often covering half a square mile.

Above photo: Casualty Clearing Station (IWM)

A CCS would normally accommodate a minimum of fifty beds and 150 stretchers and could cater for 200 or more wounded and sick at any one time. Later in the war a CCS would be able to take in more than 500 and up to 1000 when under pressure. Initially the wounded were transported to the CCS in horse-drawn ambulances – a painful journey, and over time motor vehicles or even a narrow-gauge railway were used. Often the wounded poured in under dreadful conditions, the stretchers being placed on the floor in rows with barely room to stand between them

Gas was first used as a weapon at Ypres in April 1915 and thereafter as a weapon on both sides. Patients were brought in to the CCS suffering from the effects and poisoning of chlorine, phosgene and mustard gas among others.

From the CCS men were transported en masse in ambulance trains, road convoys or by canal barges to the large base hospitals near the French coast or to a hospital ship heading for England.

Ambulance Train

These trains transported the wounded from the CCSs to base hospitals near or at one of the channel ports. In 1914 some trains were composed of old French trucks and often the wounded men lay on straw without heating and conditions were primitive. Others were French passenger trains which were later fitted out as mobile hospitals with operating theatres, bunk beds and a full complement of QAIMNS (Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service) nurses, RAMC doctors and surgeons and RAMC medical orderlies.

Above photo: Ambulance Train (IWM)

Emergency operations would be performed despite the movement of the train, the cramped conditions and poor lighting. Hospital carriages were also manufactured and fitted out in England and shipped to France.

Hospital barges

Many wounded were transported by water in hospital barges. Although slow, the journey was smooth and this time allowed the wounded to rest and recuperate. The barges were converted from a range of general use barges such as coal or cargo barges.

Above photo: Hospital barge (IWM)

The holds were converted to 30 bed hospital wards and nurses’ accommodation. They were heated by two stoves and provided with electric lighting which would have to be turned off at night to avoid being an easy target for German pilots. Nurses would have to make their rounds in pitch dark using a small torch.

Stationary Hospitals, General Hospitals & Base Area

Under the RAMC were two categories of base hospital serving the wounded from the Western Front.

There were two Stationary Hospitals to every Division and despite their name they were moved at times, each one designed to hold 400 casualties, and sometimes specialising in for instance the sick, gas victims, neurasthenia cases & epidemics. They normally occupied civilian hospitals in large cities and towns, but were equipped for field work if necessary.

Above photo: A Stationary Hospital, Rouen (Wikipedia)

The Stationary/General Hospitals were located near railway lines to facilitate movement of casualties from the CCSs on to the coastal ports. Large numbers were concentrated at Boulogne and Étaples. Grand hotels and other large buildings such as casinos were requisitioned but other hospitals were collections of huts, hastily constructed on open ground, with tents added as required, expanding capacity from 700 to 1,200 beds. At first there was a lack of basic facilities – no hot water, no taps, no sinks, no gas stoves and limited wash bowls.

Hospital Ships and Military & War Hospitals at home

Most hospital ships were requisitioned and converted passenger liners. Despite the excellent nursing and medical care many patients died aboard because of their extreme wounds. The risk of torpedoes and mines as they crossed the channel was very real.” (4)

Above photo: Glencastle Hospital Ship sunk by a German torpedo 1918 (Wikipedia)

On arrival at a British port the wounded were transferred to a home service ambulance train. It was at these railway stations that the British public got closest to the casualties of the war.

Above photo: Trains carry injured soldiers (5)

From there, the wounded went on to Military and War Hospitals which were divided into nine Command areas.

Having survived the journey home, Joseph Morgan arrived at Alnwick Convalescent Camp which was a large collection of wooden barracks on land adjoining Alnwick Castle in Northumberland. It had originally been built to house Northumberland Fusilier volunteers for basic training before they were to be sent into battle. By the summer of 1915 these battalions had moved to other camps and a decision was taken in the autumn to convert most of Alnwick Camp to a convalescent hospital, while still retaining some functions as a major depot for Northern Command.

Above photo: Alnwick Convalescent Camp (6)

“Flower beds were planted to make the surroundings more pleasant and to provide gardening activities for the convalescents.

It was here, also, that sports events, concerts, visits to events outside the camp and convalescents going out of camp on working parties would take place.” (7)

Above photo: Playing cricket, Alnwick Convalescent Camp (8)

On 4th November, 1918, Joseph Morgan died, aged 32. It is not known what the cause of his death was.

In the “UK Army Register Of Soldiers Effects”, Joseph Morgan left, in the form of a war gratuity, the sum of £11 1s 10d to either his mother Mary or his sister Mary. He also left £11 1s 9d to Elizabeth Pritchard. Given that the total sum of the gratuity came to more than £22, it is indicative of how long he had served in the armed forces. For terms of service, a private would receive a war gratuity of £5 for the first 12 months of service and then 10 shillings for each two months. So, if one works backwards from Joseph Morgan’s date of death, one can calculate the approximate date that he had enlisted on by using these figures. Thus, given that the war gratuity which was granted to Joseph Morgan was a large sum, one can determine that he must have received his wounds in late 1917 or 1918.

Joseph Morgan is buried at Broxwood Holy Roman Catholic Church.

Above photo: Joseph Morgan’s headstone (Lee Oxenham, CWGC)

Rory MacColl

Sources

1/ https://collectionswa.net.au/items/5aeb731d-671e-4fd6-8630-4f4e6bc223ec

2/ https://herefordshirelightinfantrymuseum.com/uploads/1916-aug.pdf

3/ https://vickersmg.blog/in-use/transport/man-carrying-the-mmg/driver/

4/ https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/articles/evacuation-of-the-wounded-in-world-war-i/

5/ https://texashistory.unt.edu/explore/collections/TBWP/

6/ https://bailiffgatecollections.co.uk/gallery/ww1-alnwick-camp-7/

7/ https://bailiffgatecollections.co.uk/gallery/ww1-alnwick-camp-7/

8/https://bailiffgatecollections.co.uk/gallery/ww1-alnwick-camp-7/